Gene Therapy’s First Out-and-Out Cure Is Here

A treatment now pending approval in Europe will be the first commercial gene therapy to provide an outright cure for a deadly disease.

The treatment is a landmark for gene-replacement technology, an idea that’s struggled for three decades to prove itself safe and practical.

Called Strimvelis, and owned by drug giant GlaxoSmithKline, the treatment is for severe combined immune deficiency, a rare disease that leaves newborns with almost no defense against viruses, bacteria, or fungi and is sometimes called “bubble boy” disease after an American child whose short life inside a protective plastic shield was described in a 1976 movie.

The treatment is different from any that’s come before because it appears to be an outright cure carried out through a genetic repair. The therapy was tested on 18 children, the first of them 15 years ago. All are still alive.

“I would be hesitant to call it a cure, although there’s no reason to think it won’t last,” says Sven Kili, the executive who heads gene-therapy development at GSK.

The British company licensed the treatment in 2010 from the San Raffaele Telethon Institute for Gene Therapy, in Milan, Italy, where it was developed and first tested on children.

On April 1, European advisors recommended that Strimvelis be allowed on the market. If, as expected, GSK wins formal authorization, it can start selling the drug in 27 European countries. GSK plans to seek U.S. marketing approval next year.

GSK is the first large drug company to seek to market a gene therapy to treat any genetic disease. If successful, the therapeutic could signal a disruptive new phase in medicine in which one-time gene fixes replace trips to the pharmacy or lifelong dependence on medication.

“The idea that you don’t have to worry about it and can be normal is extremely exciting for people,” says Marcia Boyle, founder and president of the Immune Deficiency Foundation, whose son was born with a different immune disorder, one of more than 200 known to exist. “I am a little guarded on gene therapy because we were all excited a long time ago, and it was not as easy to fool Mother Nature as people had hoped.”

Today, several hundred gene therapies are in development, and many aspire to be out-and-out cures for one of about 5,000 rare diseases caused by errors in a single gene.

Children who lack correct copies of a gene called adenosine deaminase begin to get life-threatening infections days after birth. The current treatment for this immune deficiency, known as ADA-SCID, is a bone marrow transplant, which itself is sometimes fatal, or lifelong therapy using costly replacement enzymes that cost $5,000 a vial.

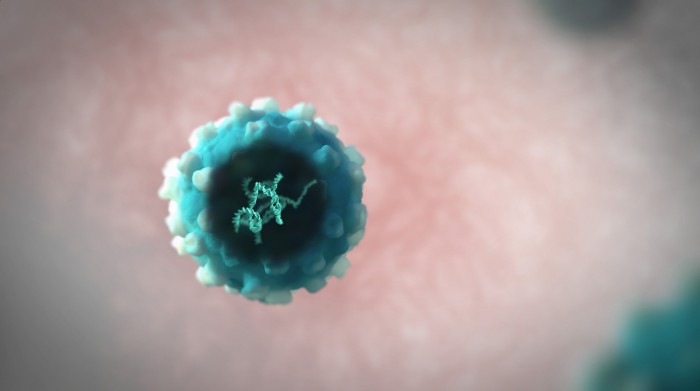

Strimvelis uses a “repair and replace” strategy, so called because doctors first remove stem cells from a patient’s bone marrow then soak them with viruses to transfer a correct copy of the ADA gene.

“What we are talking about is ex vivo gene therapy—you pull out the cells, correct them in test tube, and put the cells back,” says Maria-Grazia Roncarolo, a pediatrician and scientist at Stanford University who led the original Milan experiments. “If you want to fix a disease for life, you need to put the gene in the stem cells.”

Some companies are trying to add corrected genes using direct injections into muscles or the eye. But the repair-and-replace strategy may have the larger impact. As soon as next year, companies like Novartis and Juno Therapeutics may seek approval for cancer treatments that also use a combination of gene and cell therapy to obliterate one type of leukemia.

Overall, investment in gene therapy is booming. The Alliance for Regenerative Medicine says that globally, in 2015, public and private companies raised $10 billion, and about 70 treatments are in late-stage testing.

GSK has never sold a product so drastically different from a bottle of pills. And because ADA-SCID is one of the rarest diseases on Earth, Strimvelis won’t be a blockbuster. GSK estimates there are only about 14 cases a year in Europe, and 12 in the U.S.

Instead, the British company hopes to master gene-therapy technology, including virus manufacturing. “If we can first make products that change lives, then we can develop them into things that affect more people,” says Kili. “We believe gene therapy is an area of important future growth; we don’t want to rush or cut corners.”

Markets will closely scrutinize how much GSK charges for Strimvelis. Kili says a final decision hasn’t been made. Another gene therapy, called Glybera, debuted with a $1 million price tag but is already considered a commercial flop. The dilemma is how to bill for a high-tech drug that people take only once.

Kili says GSK’s price won’t be anywhere close to a million dollars, though it will be enough to meet a company policy of getting a 14 percent return on every dollar spent on R&D.

The connection between immune deficiency and gene therapy isn’t new. In fact, the first attempt to correct genes in a living person occurred in 1990, also in a patient with ADA-SCID.

By 2000, teams in London and France had cured some children of a closely related immune deficiency, X-linked SCID, the bubble boy disease. But some of those children developed leukemia after the viruses dropped their genetic payloads into the wrong part of the genome.

In the U.S., the Food and Drug Administration quickly canceled 27 trials over safety concerns. “It was a major step back,” says Roncarolo, and probably a more serious red flag even than the death of a volunteer named Jesse Gelsinger in a U.S. trial in 1999, which also drew attention to gene therapy’s risks.

The San Raffaele Telethon Institute for Gene Therapy presented its own results in ADA-SCID, which also affects girls, in 2002 in the journal Science. Like the French, they’d also apparently cured patients, and because of differences in their approach, they didn’t run the same cancer risk.

GSK says it is moving toward commercializing several other gene therapies for rare disease developed by the Italian team, including treatments for metachromatic leukodystrophy, a rare but rapidly fatal birth defect, and for beta thalassemia.

Kili says the general idea is to leapfrog from ultra-rare diseases to less rare ones, like beta thalassemia, hemophilia, and sickle cell disease. However, he doubts the technology will be used to treat common conditions such as arthritis or heart disease anytime soon. Those conditions are complex and aren’t caused by a defect in just one gene.

“Honestly, as we stand at the moment, I don’t think gene therapy will address all the ills or ailments of humanity. We can address [single-gene] disease,” he says. “We are building a hammer that is not that big.”

Deep Dive

Biotechnology and health

This baby with a head camera helped teach an AI how kids learn language

A neural network trained on the experiences of a single young child managed to learn one of the core components of language: how to match words to the objects they represent.

The next generation of mRNA vaccines is on its way

Adding a photocopier gene to mRNA vaccines could make them last longer and curb side effects.

An AI-driven “factory of drugs” claims to have hit a big milestone

Insilico is part of a wave of companies betting on AI as the "next amazing revolution" in biology

Ready, set, grow: These are the biotech plants you can buy now

For $73, I bought genetically modified tomato seeds and a glowing petunia.

Stay connected

Get the latest updates from

MIT Technology Review

Discover special offers, top stories, upcoming events, and more.